Stewards of this Time

Sermon on Matthew 25:14-30

The Rev. Andria Skornik

I remember back in March, when the coronavirus lockdowns first started happening, how there was this urgent sense that we needed to use this time to better ourselves. Like since we’re stuck at home, we could use the time to take up a new hobby, or master the instrument collecting dust in the basement, or finally get to all of that Russian literature we’ve been meaning to read. For parents newly tasked with overseeing school from home, people were posting color-coded schedules and other ways for parents to adapt without dropping any of the balls, or, God forbid, overdoing screen time.

There was something lovely about the way we jumped right in; determined not to let this thing get us down. It was probably one of the healthier ways to cope with all that was going on. But, as we soon learned, quarantining was not the same thing as a snow day.

It was all of the previous stress, plus life getting harder on so many levels, all while being stuck at home. For example, I remember a friend of mine saying how she felt bad she hadn’t used the time to organize shelves or de-clutter. And I said, “Are you kidding? You lost 50 hours of childcare and are still working full time. How on earth could you do one more thing?”

It’s no wonder that a few months in other approaches began circulating. Ones that’s said: It’s okay if you don’t master sourdough bread. It’s okay if your kids are watching more TV than you’d like or if you aren’t getting through all of the assigned curriculum. It’s okay to scale back those ambitions and simply make it through.

But what about now? We are now 9 months into this. Just this last week the governor announced we’re going into another lockdown. So how do we look at this time? What should we expect of ourselves? How do we judge our actions and know we’ve done the right thing?

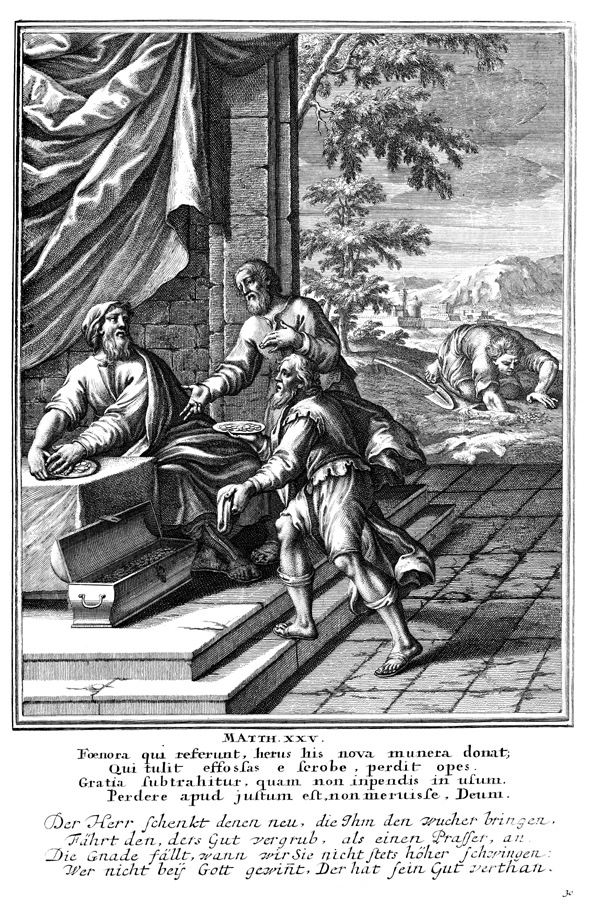

In a way, these are the very questions raised in this morning’s parable from Matthew. Now, I have to admit, I’ve always had a hard time with this parable. If I didn’t have to preach on it, I probably would’ve shut the Bible after the outer darkness part and walked away. It’s hard not to take it as a parable about eternal salvation and divine judgement; the message being we’d better be good stewards, perform well in our Christianity or else. Or that God is a shrewd, merciless master who’s just waiting for us to mess up and give us what we deserve.

But that’s not what this parable is about. It’s the accusation of the third servant — the one who buries his treasure — to be sure. He’s the one who accuses the master of being a harsh, greedy man. But in fact, at the outset of the story, the master shows himself to be very generous. He leaves each of his workers with huge sums of money. One talent was equivalent to 20 years wages or more. Allowing them to invest it would’ve been giving them a tremendous opportunity. Leaving them with so much also showed a great deal of trust in them. And that he chose to put it into their care in his absence suggests he believed in them to do great things.

Clearly, the master’s goal wasn’t to punish servants. He was looking for them to take care of what was his and do the best of it in his absence, whatever that meant for them. He says to the third servant that he would’ve been fine were the servant to put the money in the bank to get the lowest interest. We can speculate that the Master would’ve been fine if the servant had tried to invest the money and lost it, as long as he had made an effort. The worst thing for him to do was to do nothing.

Since our faith tells us that salvation is an undeserved, unearned gift, and that God’s love is unconditional — nothing we say can make God love us more or less than God already does — this text cannot be about earning our salvation or performing our way into God’s good graces. We must begin reading every scripture with the assumption that we are already in God’s grace. Instead we should see this as a parable about time. Like the parable of the ten bridesmaids last week addressing Matthew’s community as they waited for the second coming, this parable is about what we as Christians do with the time before Christ’s return.

Like with the master, God has gone away. But in this case, God has left the world in our care. The expectation is that we will do what we can to make it more than it was before. God entrusts us with this great task. But it’s not so that we can be judged on our success or failure. It’s because God genuinely cares about the outcome. God wants us to do well because God wants the poor to be lifted up. God wants us to do well because God wants there to be a correction where people are being wronged. God wants us to do well because God wants this to be a world where people feel safe to be themselves.

God wants us to do well because God wants this earth to be a good home for all the generations of humanity. God wants us to do well because God wants love to prevail in every circumstance. God wants us to do well because God cares so much about this earth and all that’s in it. God imparts us with this great opportunity and responsibility because God trusts in us, believes in us, and is rooting for us.

So what about now? In this week where the surge in cases and heightened restrictions has taken many of us back to those early days of the pandemic, but now much further in I wonder if there is a way we can look at this time. Perhaps not with the same manic ambition we started with. With tempered expectations and grace for our limitations.

With a greater understanding of the challenges we face. But also, not losing sight of the opportunity in this time we’ve been entrusted with.

It reminds me how early on there was a poem written about the pandemic that went viral. It begins,

“And the people stayed home. And read books, and listened, and rested, and exercised, and made art, and played games, and learned new ways of being, and were still...”

That part sounds like the mood of early in the pandemic. When we were entering into the first beautiful days of spring, and the novelty was still there. But it goes on..

“And [the people] listened more deeply. Some meditated, some prayed, some danced. Some met their shadows. And the people began to think differently.

And the people healed. And, in the absence of people living in ignorant, dangerous, mindless, and heartless ways, the earth began to heal.

And when the danger passed, and the people joined together again, they grieved their losses, and made new choices, and dreamed new images, and created new ways to live and heal the earth fully, as they had been healed.”

The second part of the poem is where we are and what we need to see now. Not that we’ve arrived, or will. The ignorant, dangerous, mindless ways haven’t gone away with the pandemic. But there is something in the disruption. In shaking things up. We are getting a unique chance to make changes. To reckon with things we previously haven’t seen or wanted to see. We are getting a chance to form new patterns. To enter into solidarity with people we would’ve never crossed paths with in our past lives. To practice radical acceptance and grace. To learn to lean on each other, and shed some of our individualism for the interdependence of community. We are learning to grieve our losses, of which there are many. Maybe learning to really grieve and give ourselves the adequate space for it for the first time. But then to pick ourselves back up. To heal. To dream and create something new.

God was entrusted this time to us. What does it look like to invest it, make the most of it, try to do our best with it, knowing God is rooting for us, trusting us, believing in us?

Influential Sources

Kitty O’Meara, “And the People Stayed Home”

https://www.irishcentral.com/culture/irish-american-teachers-poem-covid19-outbreak